From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Anna Eleanor Roosevelt | |

White House portrait | |

| | |

| In office December 31, 1946 – December 31, 1952 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

|---|---|

| | |

| In office 1946–52 | |

| Preceded by | New creation |

| Succeeded by | Charles Malik |

| | |

| In office 1961–62 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Esther Peterson |

| | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Lou Henry Hoover |

| Succeeded by | Elizabeth "Bess" Wallace Truman |

| | |

| In office January 1, 1929 – December 31, 1932 | |

| Preceded by | Catherine A. Dunn |

| Succeeded by | Edith Louise Altschul |

| | |

| Born | October 11, 1884 New York, New York United States |

| Died | November 7, 1962 (aged 78) New York, New York United States |

| Resting place | Hyde Park, New York |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Children | Anna Eleanor, James, Elliott, Franklin, John |

| Occupation | First Lady, diplomat, activist |

| Religion | Episcopal |

| Signature | |

In the 1940s, Roosevelt was one of the co-founders of Freedom House and supported the formation of the United Nations. Roosevelt founded the UN Association of the United States in 1943 to advance support for the formation of the UN. She was a delegate to the UN General Assembly from 1945 and 1952, a job for which she was appointed by President Harry S. Truman and confirmed by the United States Senate. During her time at the United Nations she chaired the committee that drafted and approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. President Truman called her the "First Lady of the World" in tribute to her human rights achievements.[1]

Active in politics for the rest of her life, Roosevelt chaired the John F. Kennedy administration's ground-breaking committee which helped start second-wave feminism, the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. She was one of the most admired people of the 20th century, according to Gallup's List of Widely Admired People.[2]

[edit] Personal life

[edit] Early life

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was born on West 37th Street in New York City, the daughter of Elliott Roosevelt and Anna Hall Roosevelt. She was named Anna after her mother and her aunt Anna Cowles; Eleanor after her father, and was nicknamed "Ellie" or "Little Nell".[3] From the beginning, Eleanor preferred to be called by her middle name.Two brothers, Elliott Roosevelt, Jr. (1889–93) and Hall Roosevelt (1891–1941) were born later. She also had a half brother, Elliott Roosevelt Mann (died 1941), who was born to Katy Mann, a servant employed by the family.[4]

Roosevelt was born into a world of immense wealth and privilege, as her family was part of New York high society called the "swells".[5]

Roosevelt was so sober a girl that her mother nicknamed her "Granny". Her mother died from diphtheria when Roosevelt was eight and her father, an alcoholic confined to a sanitarium, died less than two years later. Her brother Elliott Jr. died from diphtheria, just like his mother. Thus, she was raised from early adolescence by her maternal grandmother, Mary Ludlow Hall (1843–1919) at Tivoli, New York. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Eleanor Roosevelt, Joseph P. Lash describes her during this period of childhood as insecure and starved for affection, considering herself "ugly".[5] Nevertheless, even at 14, Roosevelt understood that one's prospects in life were not totally dependent on physical beauty, writing wistfully that "no matter how plain a woman may be if truth and loyalty are stamped upon her face all will be attracted to her."[6]

Roosevelt was tutored privately and, at the age of 15, with the encouragement of her father's sister, her aunt "Bamie", the family decided to send her to Allenswood Academy, a private finishing school outside London, England. The headmistress, Marie Souvestre, was a noted feminist educator who sought to cultivate independent thinking in the young women in her charge. Eleanor learned to speak French fluently and gained self-confidence. Her first-cousin Corinne Robinson, whose first term at Allenswood overlapped with Eleanor's last, said that when she arrived at the school, Eleanor was "everything". She would later study at The New School in the 1920s.[7]

[edit] Marriage and family life

In 1902 at age 17, Roosevelt returned to the United States, ending her formal education. On December 14, 1902, Roosevelt was presented at a debutante ball at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. She was later given a debutante party. As a member of The New York Junior League, she volunteered as a social worker in the East Side slums of New York. Roosevelt was among the League's earliest members, having been introduced to the organization by her friend, and organization founder, Mary Harriman.That same year Roosevelt met her father's fifth cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was overwhelmed when the 20-year-old dashing Harvard University student demonstrated affection for her. Following a White House reception and dinner with her uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt, on New Year's Day, 1903, Franklin's courtship of Eleanor began. She later brought Franklin along on her rounds of the squalid tenements, a walking tour that profoundly moved the theretofore sheltered young man.

In November 1904, they became engaged, although the engagement was not announced until December 1, 1904, at the insistence of Franklin's mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt. She opposed the union. "I know what pain I must have caused you," Franklin wrote his mother of his decision. But, he added, "I know my own mind, and known it for a long time, and know that I could never think otherwise." Sara took her son on a cruise in 1904, hoping that a separation would squelch the romance, but Franklin returned to Eleanor with renewed ardor. The wedding date was fixed to accommodate President Roosevelt, who agreed to give the bride away. Her uncle's presence focused national attention on the wedding.

Roosevelt, age 20, married Franklin Roosevelt, age 23, her fifth-cousin once removed, on March 17, 1905 (St. Patrick's Day), at the adjoining townhouses of Mrs. Elizabeth Livingston Ludlow and her daughter, Susan "Cousin Susie" Parish in New York City. The Reverend Dr. Endicott Peabody, the groom's headmaster at Groton School, performed the services. The couple spent a preliminary honeymoon of one week at Hyde Park, then set up housekeeping in an apartment in New York. That summer they went on their formal honeymoon, a three-month tour of Europe.

Returning to the U.S., the newlyweds settled in New York City, in a house provided by Franklin's mother, as well as at the family's estate overlooking the Hudson River in Hyde Park, New York. Roosevelt deferred to her mother-in-law in virtually all household matters. She did not gain a measure of independence until her husband was elected to the state senate and the couple moved to Albany, New York. Eleanor Roosevelt was also a member of the Order of the Eastern Star.

The Roosevelts had six children, five of whom survived infancy:

- Anna Eleanor, Jr. (1906–75) – journalist, public relations official.

- James (1907–91) – businessman, congressman, author.

- Franklin Delano, Jr. (b./d. 1909)

- Elliott (1910–90) – businessman, mayor, author.

- Franklin Delano Jr. (1914–88) – businessman, congressman, farmer.

- John Aspinwall (1916–81) – merchant, stockbroker.

It was Eleanor who prodded Franklin to return to active life. To compensate for his lack of mobility, she overcame her shyness to make public appearances on his behalf and thereafter served him as a listening post and barometer of popular sentiment.

[edit] Relationship with mother-in-law

Roosevelt and her future mother-in-law Sara Delano Roosevelt in 1904

From Sara's perspective, Eleanor was relatively young and inexperienced and lacked maternal support. Sara felt she had much to teach her new daughter-in-law on what a young wife should know. Eleanor, while sometimes resenting Sara's domineering nature, nevertheless highly valued her opinion in the early years of her marriage until she developed the experience and confidence from the school of marital "hard knocks". Historians continue to study the reasons Eleanor allowed Sara to dominate their lives, especially in the first years of the marriage. Eleanor's income was more than half of that of her husband's when they married in 1905 and the couple could have lived still relatively luxuriously without Sara's financial support.[10]

Sara was determined to ensure her son's success in all areas of life including his marriage. Sara had doted on her son to the point of spoiling him, and now intended to help him make a success of his marriage with a woman that she evidently viewed as being totally unprepared for her new role as chatelaine of a great family. Sara would continue to give huge presents to her new grandchildren, but sometimes Eleanor had problems with the influence that came with "mother's largesse."[5]

[edit] Tensions with "Oyster Bay Roosevelts"

| | This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2010) |

Alice often hosted dinner parties at her Washington, D. C. home, where she promoted the affair between Franklin and Lucy Mercer. Alice would invite both Franklin and Lucy to dine—especially when Eleanor was out of town. Alice must have savored this underhanded revenge. "He deserved a good time," Alice once said of FDR; after all, "he was married to Eleanor."[11]

That said, Alice was not particularly enamored with FDR either; she described Franklin as "two-thirds mush and one-third Eleanor". When Franklin was inaugurated president in 1933, Alice was invited to attend along with her brothers, Kermit and Archie. When Eleanor Roosevelt died in 1962, her cousin Ethel Derby wrote that she would not attend Mrs. Roosevelt's funeral because she did not love her.

[edit] Franklin's affair and Eleanor's relationships

Despite its happy start and Roosevelt's intense desire to be a loving and loved wife, their marriage almost disintegrated over Franklin's affair with his wife's social secretary Lucy Mercer (later Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd).[12] When Eleanor learned of the affair from Mercer's letters, which she discovered in Franklin's suitcases in September 1918, she was brought to despair and self-reproach. She told Franklin she would insist on a divorce if he did not immediately end the affair. He knew that a divorce would not reflect well on his family, so he ended the relationship.So implacable was Sara's opposition to divorce that she warned her son she would disinherit him. Corinne Robinson, and Louis McHenry Howe, Franklin's political advisors, were also influential in persuading Eleanor and Franklin to save the marriage for the sake of the children and Franklin's political career. The idea has been put forth that, because Mercer was a Catholic, she would never have married a divorced Protestant. Her relatives maintain that she was perfectly willing to marry Franklin. Her father's family was Episcopal and her mother had been divorced.[13] While Franklin agreed never to see Mercer again, she began visiting him in the 1930s and was with Franklin at Warm Springs, Georgia when he died on April 12, 1945.[14]

Although the marriage survived, Roosevelt emerged a different woman, coming to the realization that she could achieve fulfillment only through her own influence.[5] Ironically, her husband's paralysis would soon place his political future partially in her hands, requiring her to play an active role in New York State Democratic politics. It was a move she had been gradually making, having long held considerable, if repressed, interest in politics and social issues. During the 1920s, as Franklin dealt with his illness, with the coaching of his trusted political adviser Louis McHenry Howe, she became a prominent face among Democratic women and a force in New York state politics.

Although she and her husband were often separated by their activities during these years, their relationship, though at times strained, was close, despite Eleanor's insistence on severing their physical relationship after discovering Franklin's affair. He was to often pay tribute to her care for him during the worst days of his illness, her help to him in his work, encouraging his staff and others to view them as a team, and to her ability to connect with various groups of people. He respected her intelligence and honest and sincere desire to improve the world, even if he sometimes found her too insistent and lacking in political suppleness. "Your back has no bend," he once told her.

In 1926, Franklin took great pleasure in presenting Eleanor with a cottage on the Hyde Park estate, called "The Stone Cottage", where she and her closest friends at the time, Nancy Cook and Marion Dickerman, could escape from the main house. In 1928, she was urged by New York Governor Al Smith, who was the Democratic candidate for president, to press her husband to run for New York Governor in his place. After repeated urgings, she finally placed a call to Franklin, who gleefully told her he'd been successfully dodging all of Smith's frantic calls. She handed the phone to Smith and the rest is history.

Though pleased for Franklin, Eleanor was increasingly despondent as he resumed his career, fearing she would be forced to take on an increasingly ceremonial role. During the 1932 campaign, Louis Howe was horrified to read a note about her feelings of uselessness she had sent to a friend. Howe tore it up, warning the friend to say nothing. An offer by Eleanor to Franklin after the election to take on some of his mail was rebuffed, because it might have offended his secretary, Marguerite "Missy" LeHand.

However, Franklin and Howe had larger plans for Eleanor. The skills she had developed as a political trooper for the women's branch of the New York State Democratic party as well as during her time as New York state's First Lady were to stand her in good stead. Howe made immediate use of her in dealing with the problem of the Bonus Army, unemployed veterans of World War I who had marched and encamped in Washington, D.C., demanding payment of the bonuses promised to them for their wartime service. President Herbert Hoover had viewed them as a dangerous, Communist-inspired group and sent the Army under Commander-in-Chief Douglas MacArthur to drive the group out with tear gas. Roosevelt and Howe took a radically different approach sending food, friendly greetings, and Eleanor. "Hoover sent the Army, Roosevelt sent his wife" became one of the classic lines of the New Deal era.

In 1933, Roosevelt had a very close relationship with Lorena Hickok, a reporter who had covered her during the campaign and early days of the Roosevelt administration and sensed her discontent, which spanned her early years in the White House.[15] On the day of Eleanor's husband's inauguration, she was wearing a sapphire ring that Hickok had given her.[15]

Later, when their correspondence was made public, it became clear that Roosevelt would write such endearments as, "I want to put my arms around you & kiss you at the corner of your mouth."[16] It is unknown if her husband was aware of the relationship, which scholar Lillian Faderman has asserted to be lesbian.[15] Hickok's relationship with Roosevelt has been the subject of much speculation but it has not been determined whether the two were romantically connected.[17]

Roosevelt with President Ramon Magsaysay, the 7th President of the Philippines, and his wife at the Malacañang Palace in 1955.

Roosevelt was 44 years old when she met Miller, 32, in 1929. According to several of Franklin's biographers, Miller became her friend as well as official escort. He taught her different sports, such as diving and riding, and coached her tennis game. There is some speculation that the relationship was a romance rather than a friendship. Blanche Wiesen Cook writes that Miller was Eleanor's "first romantic involvement" in her middle years. James Roosevelt wrote, "I personally believe they were more than friends." Miller denied a romantic relationship.

Roosevelt's friendship with Miller happened during the same years as her husband's relationship with his secretary, Missy LeHand. Smith writes, "[r]emarkably, both ER and Franklin recognized, accepted, and encouraged the arrangement… Eleanor and Franklin were strong-willed people who cared greatly for each other's happiness but realized their own inability to provide for it."[19] Their relationship is said to have continued until her death in 1962. They are thought to have corresponded daily, but all letters have been lost. According to rumors (Elliott and Franklin, Jr. are believed to have actually seen the letters) the letters were anonymously purchased and destroyed or locked away when she died.[20] In later years, Roosevelt was said to have developed a romantic attachment to her physician, David Gurewitsch, though it was likely limited to a deep friendship.

[edit] Public life before the White House

Following Franklin's paralytic illness attack in 1921, Eleanor began serving as a stand-in for her incapacitated husband, making public appearances on his behalf, often carefully coached by Louis Howe, with increasingly successful results. She also started working with the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL), raising funds in support of the union's goals: a 48-hour work week, minimum wage, and the abolition of child labor.[5] Throughout the 1920s, Eleanor became increasingly influential as a leader in the New York State Democratic Party while Franklin used her contacts among Democratic women to strengthen his standing with them, winning their committed support for the future. In 1924, she actively campaigned for Alfred E. Smith in his successful re-election bid as governor of New York State. By 1928, Eleanor was actively promoting Smith's candidacy for president and Franklin's nomination as the Democratic Party's candidate for governor of New York, succeeding Smith. Although Smith lost, Franklin won handily and the Roosevelts moved into the governor's mansion in Albany, New York.In the 1920s, Roosevelt taught literature and American history at the Todhunter School for Girls, now the Dalton School, in New York City.

[edit] First Lady of the United States (1933–45)

Following the Presidential inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt ("FDR") on March 4, 1933, Eleanor became First Lady of the United States. Having seen the strictly circumscribed role and traditional protocol of her aunt, Edith Roosevelt, during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), Roosevelt set out on a different course. With her husband's strong support, despite criticism of them both, she continued with the active business and speaking agenda she had begun before becoming First Lady, in an era when few women had careers. She was the first to hold weekly press conferences and started writing a widely syndicated newspaper column, "My Day"[21] at the urging of her literary agent, George T. Bye.[citation needed]Roosevelt maintained a heavy travel schedule over her 12 years in the White House, frequently making personal appearances at labor meetings to assure Depression-era workers that the White House was mindful of their plight. In one widely-circulated cartoon of the time from The New Yorker magazine (June 3, 1933) lampooning the peripatetic First Lady, an astonished coal miner, peering down a dark tunnel, says to a co-worker "For gosh sakes, here comes Mrs. Roosevelt!"[22][23]

Roosevelt in front of the White House with Madame Chiang Kai-shek in 1943

One social highlight of the Roosevelt years was the 1939 visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the first British monarchs to set foot on U.S. soil. The Roosevelts were criticized in some quarters for serving hot dogs to the royal couple during a picnic at Hyde Park.[24]

Standing at a height of 5'11 1/2, Eleanor Roosevelt is the tallest First Lady in American History.

[edit] Roosevelt and the media

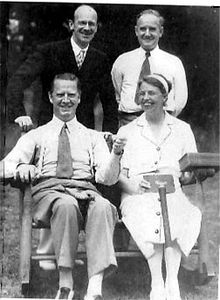

Eleanor Roosevelt, George T. Bye (her literary agent, upper right), Deems Taylor (upper left), Westbrook Pegler (lower left), Quaker Lake, Pawling, New York (home of Lowell Thomas), 1938

At the time of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency, the same time that Eleanor served as First Lady, most women found themselves within the walls of their homes. Only 25% of women worked outside the home. The vast majority of women, that being 75%, were unpaid homemakers. Mrs. Roosevelt used her weight in the media as a way to connect with women who found themselves in domestic isolation. With this in mind, Eleanor used three mediums to keep in touch with her female followers. She used the press conference, a daily newspaper column, and magazine articles. These three means opened up the communication into a two-way channel.

Although the First Lady initially wanted to be the voice of the White House to female journalists, Mrs. Roosevelt’s news was often about humanitarian concerns. Her reports stayed true to those issues of the American woman, such as unemployment, poverty, education, rural life, and the role of women in society.

Eleanor held 348 press conferences over the span of her husband’s 12-year presidency. Men were not welcome into these meetings because women as well as female journalists were discriminated against. Roosevelt felt that her information should only be available to those who were not seen as fit to hear information from a man. These conferences made it acceptable for women to think in a broader spectrum, one that was outside of their overwhelming domestic lifestyle.

Roosevelt’s newspaper column “My Day,” ran from 1936 to 1962. The column was seen as a diary of her daily activities. In archiving her life happenings, Eleanor’s column often brought up the same issues as those of her press conferences. Those concerns based upon the public welfare often intrigued readers but discouraged political experts who said it lacked intellectualism. “My Day” also kept a record of the First Lady’s hectic schedule. The column became somewhat of a newsletter for women in politics.

In the spring of 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt signed with Woman's Home Companion, a leading women’s magazine, to do a monthly column. Roosevelt used the column to answer mail she had received from readers. The allotted space allowed her to discuss more social concerns such as prenatal care, better working conditions, American holidays, and New Deal programs to insure home mortgages. Readers petitioned for help of all kinds to which she responded graciously. During her time in the White House, Eleanor published over sixty articles in magazines with national circulations.

Eleanor Roosevelt recognized a need for American women to take part in media communications. As a public figure she harnessed the power of the media and used it to interact with the women of America. By use of this medium, Roosevelt attempted to break the barriers of the domestic household and broaden the spectrum of women. She also set a precedent for following first ladies to remain in touch with the nation by means of the media. [25] [26] [27]

[edit] World War II

Roosevelt flying with Tuskegee Airman Charles "Chief" Anderson in March 1941

In 1943, Roosevelt was sent on a trip to the South Pacific, scene of major battles against the Japanese. The trip became a legend, her fortitude in patiently visiting thousands of wounded servicemen through miles of hospitals causing even the hard-bitten Admiral Halsey, who had opposed her visit initially, to sing her praises. A Republican serviceman insisted to a colleague that he and the other soldiers who'd encountered her warmth would gladly repay any grumbling civilians for whatever gasoline and rubber her visit had cost.

Desirous of improving relations with other countries in the Western Hemisphere, Roosevelt embarked on a whirlwind tour of Latin American countries in March 1944. For the trip, which would cover a number of nations and involve thousands of air miles, she was given a U.S. government-owned C-87A aircraft, the Guess Where II, a VIP transport plane which had originally been built to carry her husband abroad. After reviewing the poor safety record of that aircraft type (many had either caught fire or crashed during the war), the Secret Service forbade the use of the plane for carrying the president, even on trips of short duration, but approved its use for the First Lady.[28]

Roosevelt especially supported more opportunities for women and African-Americans, notably the Tuskegee Airmen in their successful effort to become the first black combat pilots. She visited the Tuskegee Air Corps Advanced Flying School in Alabama and, at her request, flew with a black student pilot for more than an hour, which had great symbolic value and brought visibility to Tuskegee's pilot training program.[29] She also arranged a White House meeting in July 1941 for representatives of the Tuskegee flight school to plead their cause for more support from the military establishment in Washington.

Roosevelt was a strong proponent of the Morgenthau Plan to de-industrialize Germany in the postwar period,[30][31][32] and was in 1946 one of the few prominent individuals to remain a member of the campaign group lobbying for a harsh peace for Germany.[33]

[edit] Years after the White House

After the President's death by stroke on April 12, 1945, at Warm Springs, Georgia, while she remained in Washington, Roosevelt learned that Lucy Rutherfurd had been with FDR when he died.[34] Her biographer, Joseph P. Lash, called it a "bitter discovery" and wrote that Roosevelt alluded to this in her memoir of the White House years, This I Remember:All human beings have failings, all human beings have needs and temptations and stresses. Men and women who live together through long years get to know one another's failings; but they also come to know what is worthy of respect and admiration ... He might have been happier with a wife who was completely uncritical. That I was never able to be, and he had to find it in some other people. Nevertheless, I think I sometimes acted as a spur, even though the spurring was not always wanted or welcome.[34]

[edit] United Nations

Roosevelt speaking at the United Nations in July 1947.

In 2008, a plaque commemorating ER's driving force in the creation and adoption of the UDHR, was inaugurated by Swiss Federal Councillor, Micheline Calmy-Rey in Geneva. This "Magna Carta of our time" was ER's greatest success – for she forged a common standard of achievement among delegates who had differing government systems, philosophies, religions, cultures and economic levels.

Politically, Roosevelt supported Adlai Stevenson for president in 1952 and 1956 and urged his renomination in 1960. She resigned from her UN post in 1953, when Dwight D. Eisenhower became President.

Although Roosevelt had reservations about John F. Kennedy for his failure to condemn McCarthyism, she supported him for president against Richard Nixon. Kennedy in turn reappointed her to the United Nations, 1961–1962.

[edit] Relations with the Catholic Church

In July 1949, Roosevelt had a public disagreement with Francis Joseph Spellman, the Catholic Archbishop of New York, which was characterized as "a battle still remembered for its vehemence and hostility".[41][42] In her columns, Roosevelt had attacked proposals for federal funding of certain nonreligious activities at parochial schools, such as bus transportation for students. Spellman cited the Supreme Court's decision which upheld such provisions, accusing her of anti-Catholicism. Most Democrats rallied behind Roosevelt, and Spellman eventually met with her at her Hyde Park home to quell the dispute. However, Roosevelt maintained her belief that Catholic schools should not receive federal aid, evidently heeding the writings of secularists such as Paul Blanshard.[41] Privately, Roosevelt said that if the Catholic Church gained school aid, "Once that is done they control the schools, or at least a great part of them."[41]During the Spanish Civil War, Roosevelt favored the republican Loyalists against General Francisco Franco's Nationalists; after 1945, she opposed normalizing relations with Spain.[43] She told Spellman bluntly that "I cannot however say that in European countries the control by the Roman Catholic Church of great areas of land has always led to happiness for the people of those countries."[41] Her son Elliott Roosevelt suggested that her "reservations about Catholicism" were rooted in her husband's sexual affairs with Lucy Mercer and Missy LeHand, who were both Catholics.[44]

Roosevelt's defenders, such as biographer Joseph P. Lash, deny that she was anti-Catholic, citing her public support of Al Smith, a Catholic, in the 1928 presidential campaign and her statement to a New York Times reporter that year quoting her uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt, in expressing "the hope to see the day when a Catholic or a Jew would become president".[45]

[edit] Postwar politics

In the late 1940s, Roosevelt was courted for political office by Democrats in New York and throughout the country.At first I was surprised that anyone should think that I would want to run for office, or that I was fitted to hold office. Then I realized that some people felt that I must have learned something from my husband in all the years that he was in public life! They also knew that I had stressed the fact that women should accept responsibility as citizens. I heard that I was being offered the nomination for governor or for the United States Senate in my own state, and even for Vice President. And some particularly humorous souls wrote in and suggested that I run as the first woman President of the United States! The simple truth is that I have had my fill of public life of the more or less stereotyped kind.[46]

Roosevelt with Frank Sinatra in 1960

In 1954, Tammany Hall boss Carmine DeSapio defeated Roosevelt's son, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr., during the New York Attorney General elections. Roosevelt grew increasingly disgusted with DeSapio's political conduct through the rest of the 1950s. Eventually, she would join with her old friends Herbert Lehman and Thomas Finletter to form the New York Committee for Democratic Voters, a group dedicated to enhancing the democratic process by opposing DeSapio's reincarnated Tammany. Their efforts were eventually successful, and DeSapio was removed from power in 1961.[47]

When President Truman backed New York Governor W. Averell Harriman, who was a close associate of DeSapio, for the Democratic presidential nomination, Roosevelt was disappointed but continued to support Stevenson, who ultimately won the nomination. She backed Stevenson once again in 1960 primarily to block John F. Kennedy, who eventually received the presidential nomination.[41] Nevertheless, she worked hard to promote the Kennedy-Johnson ticket in 1960 and was appointed to policy-making positions by the young president, including the National Advisory Committee of the Peace Corps.[48]

By the 1950s, Roosevelt's international role as spokesperson for women led her to stop publicly attacking the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), though she never supported it. In 1961, President Kennedy’s undersecretary of labor, Esther Peterson proposed a new Presidential Commission on the Status of Women. Kennedy appointed Roosevelt to chair the commission, with Peterson as director. Roosevelt died just before the commission issued its final report. It concluded that female equality was best achieved by recognition of gender differences and needs, and not by an Equal Rights Amendment.[49]

Throughout the 1950s, Roosevelt also embarked on countless national and international speaking engagements, continued to pen her newspaper column, and made appearances on television and radio broadcasts. She averaged one hundred and fifty lectures a year throughout the fifties; many of which were devoted to her activism on behalf of the United Nations.[50] On May 6, 1959, she addressed a crowd of 1,500 students, faculty, and community members at Ball State Teachers College (now Ball State University) in which Roosevelt stressed the urgency of understanding other peoples of the world. Roosevelt stated, “This is what it means to face world leadership. The government cannot do it for us. Many of us do not even know the whole of our own little communities. It would help us all over the world to understand people.”[51]

Roosevelt was responsible for the eventual establishment, in 1964, of the 2,800 acre (11 km2)[52] Roosevelt Campobello International Park on Campobello Island, New Brunswick, Canada. This followed a gift of the Roosevelt summer estate to the Canadian and American governments.

[edit] Honors and awards

Roosevelt on a 1963 stamp

In 1958, Folkways Records released an album by Roosevelt of her documentary on the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. A decade later, she was awarded one of the United Nations Human Rights Prizes. There was an unsuccessful campaign to award her a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize; however, a posthumous nomination has never been considered for the award.[53]

In 1960, Greer Garson played Roosevelt in the movie Sunrise at Campobello, which portrayed Eleanor's instrumental role during Franklin's bout with polio and his protracted struggle to reenter politics in its aftermath.

Westmoreland Homesteads, located in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, was created on April 13, 1934, as one of a series of “subsistence homesteads” under the National Industrial Recovery Act. In 1937, the community changed its name to Norvelt (EleaNOR RooseVELT), following a visit by the first lady. The Norvelt fireman's hall is called Roosevelt Hall.

Roosevelt was the first First Lady to receive honorary membership into Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Incorporated, the world's first and oldest sorority for African-American women.

[edit] Later private life

Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt's gravesite in the Rose Garden at the Springwood Estate.

Roosevelt was a member of the Brandeis University Board of Trustees, delivering the University's first commencement speech, and joined the Brandeis faculty as a visiting lecturer in international relations in 1959 at the age of 75. On November 15, 1960, she met for the last time with former U.S. President Harry S Truman and his wife, Bess Truman, at the Truman Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri. Roosevelt had raised considerable funds for the erection and dedication of the building. The Trumans would later attend Roosevelt's memorial service in Hyde Park in November, 1962.

In 1961, all volumes of Roosevelt's autobiography, which she had begun writing in 1937, were compiled into The Autobiography of Eleanor Roosevelt, which is still in print (Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80476-X).

[edit] Death

Memorial in Riverside Park, Manhattan

Her funeral at Hyde Park was attended by President John F. Kennedy and former Presidents Truman and Eisenhower. At her memorial service, Adlai Stevenson asked, "What other single human being has touched and transformed the existence of so many?" Stevenson also said that Roosevelt was someone "who would rather light a candle than curse the darkness." She was laid to rest next to Franklin at the family compound in Hyde Park, New York on November 10, 1962.

Roosevelt, who considered herself plain and craved affection as a child, had in the end transcended whatever shortcomings she felt were hers to bring comfort and hope to many, becoming one of the most admired figures of the 20th century.[1][2][5]

No comments:

Post a Comment